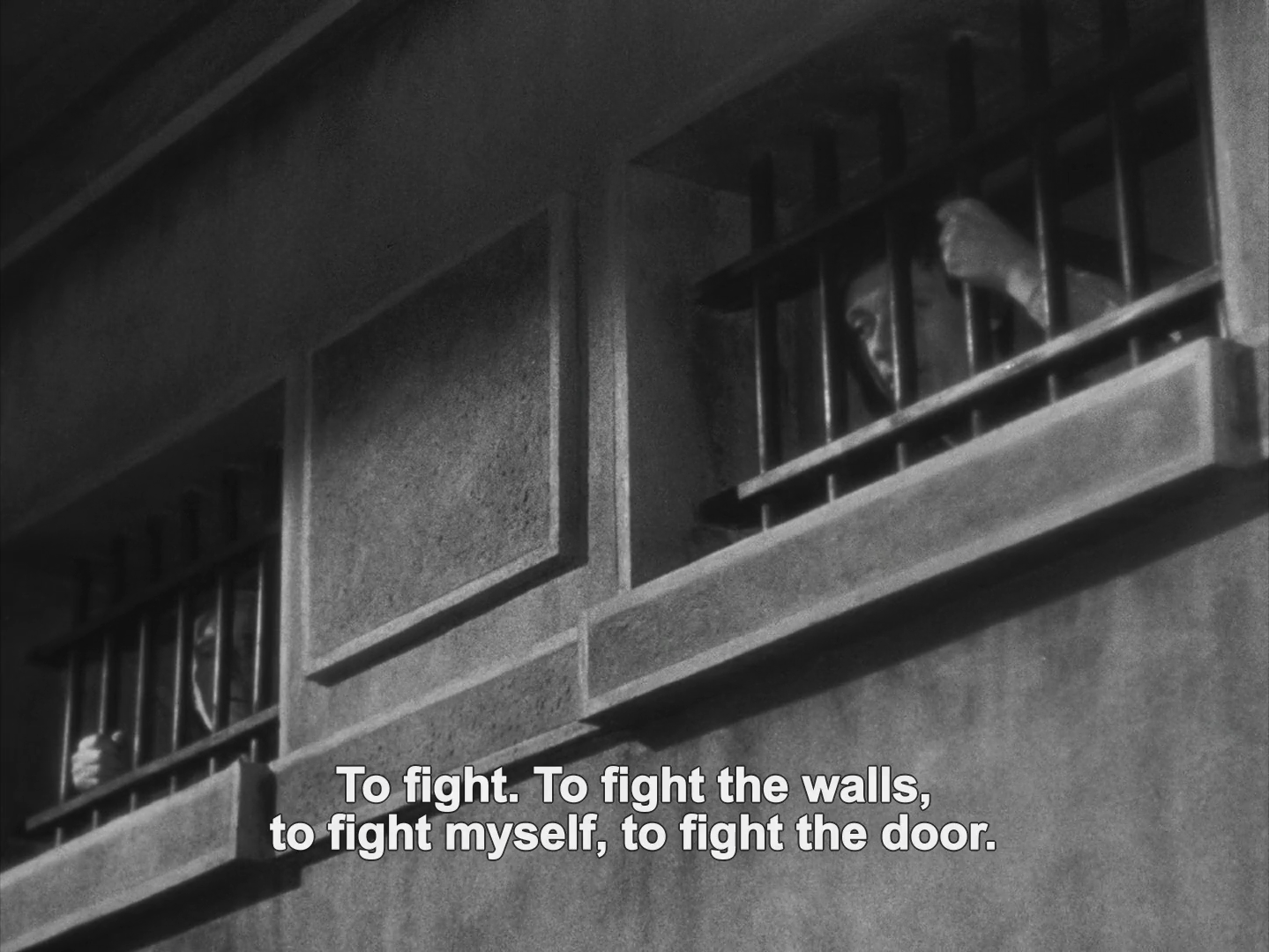

Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped: "To fight. To fight the walls, to fight myself, to fight the door."

A Man Escaped, directed by Robert Bresson, screenplay by Robert Bresson, cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel, and edit Raymond Lamy.

When asked about the importance of Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky answered, “There are many reasons I consider Bresson a unique phenomenon in the world of film. Indeed, Bresson is one of the artists who has shown that cinema is an artistic discipline on the same level as the classic artistic disciplines such as poetry, literature, painting, and music. The second reason I admire Bresson is personal. It is the significance of his work for me—the vision of the world that it expresses. This vision of the world is expressed in an ascetic way, almost laconic, lapidary I would say. Very few artists succeed in this. Every serious artist strives for simplicity, but only a few manage to achieve it. Bresson is one of the few who has succeeded. The third reason is the inexhaustibility of Bresson’s artistic form. That is, one is compelled to consider his artistic form as life, nature itself. In that sense, I find him very close to the oriental artistic concept of Zen: depth within narrowly defined limits. Working with these forms, Bresson attempts in his films not to be symbolic; he tries to create a form as inexhaustible as nature, life itself.”

All true artists fight to convey the best path of expression within their art forms. Andrei Tarkovsky admired Robert Bresson because they shared a similar spirit when it came to filmmaking, a passion for shedding light on cinema as an art form with its own language and manner of engaging and creating profound experiences for audiences. Like Tarkovsky, Bresson epitomizes the authentic artist whose self-determination brings forth unparalleled art. He follows his vision, intuition, and own set of rules for filmmaking: he follows his own quest as an artist of cinema. His simplification or in other words purification of film elements is directed to reveal cinema not as a canvas for popular and commercial moviemaking but as a unique art form that generates unique experiences. The art and the cinematic experience together are the all-in-all. He himself expressed it as, “It’s not a question of understanding, it’s a question of feeling.” Direct yourself toward the experience to be felt by the audience, and the feeling will generate meaning.

The films of Bresson are also manifestations of the insight that you the artist are your greatest asset. One needs only to visit these Koan-like statements found in his Notes on the Cinematograph to become aware of the essence of the artist. “Metteur en scène or director. The point is not to direct someone, but to direct oneself.“ “Don't think of your film apart from the resources you have made for yourself.“ “Make visible what, without you, might never have been seen.” You are your greatest tool, your greatest resource.

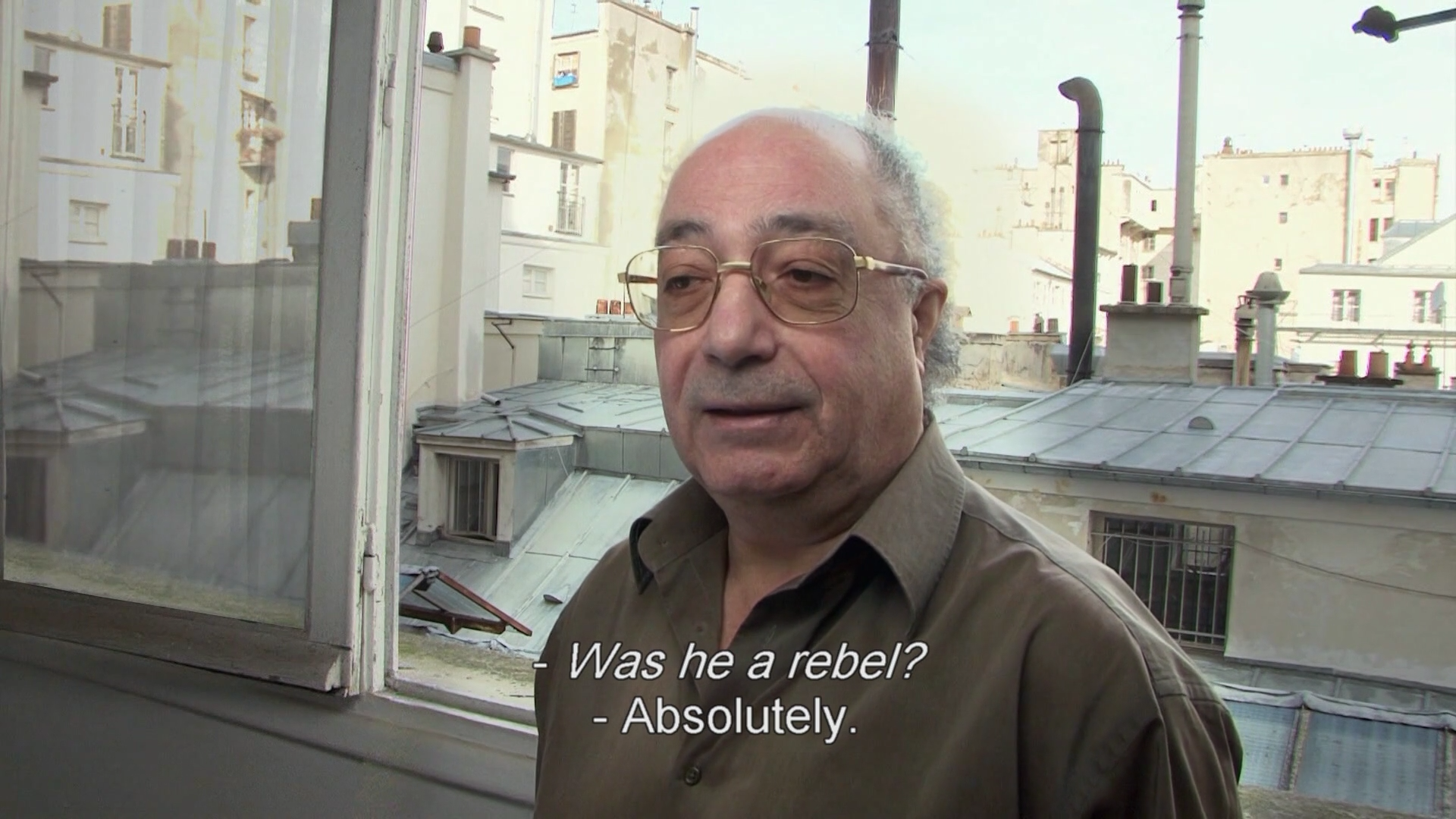

Iradj Azimi on Robert Bresson: "He was a rebel, and he remained a rebel."

Iradj Azimi speaking on Robert Bresson in The Essence of Forms shares a similar sentiment to Andrei Tarkovsky: “Robert Bresson is for me an example of a real and genuine filmmaker. He obeys only certain higher, objective laws of Art…Bresson is the only person who remained himself and survived all the pressures brought by fame.”

Creative Inspiration: All Artists Have Unique Paths

All artists have unique paths. Bresson, Tarkovsky, and Melville are three examples of artists who inspire us not only with their masterful filmmaking and timeless films but also with how they began their careers as filmmakers. It does not matter at what age you start. It does not matter from where you start. The pursuit of your dreams and passions is a never-ending quest. The right time to start is always now.

Favorite Films of Filmmakers: Andrei Tarkovsky's Top 10 Films

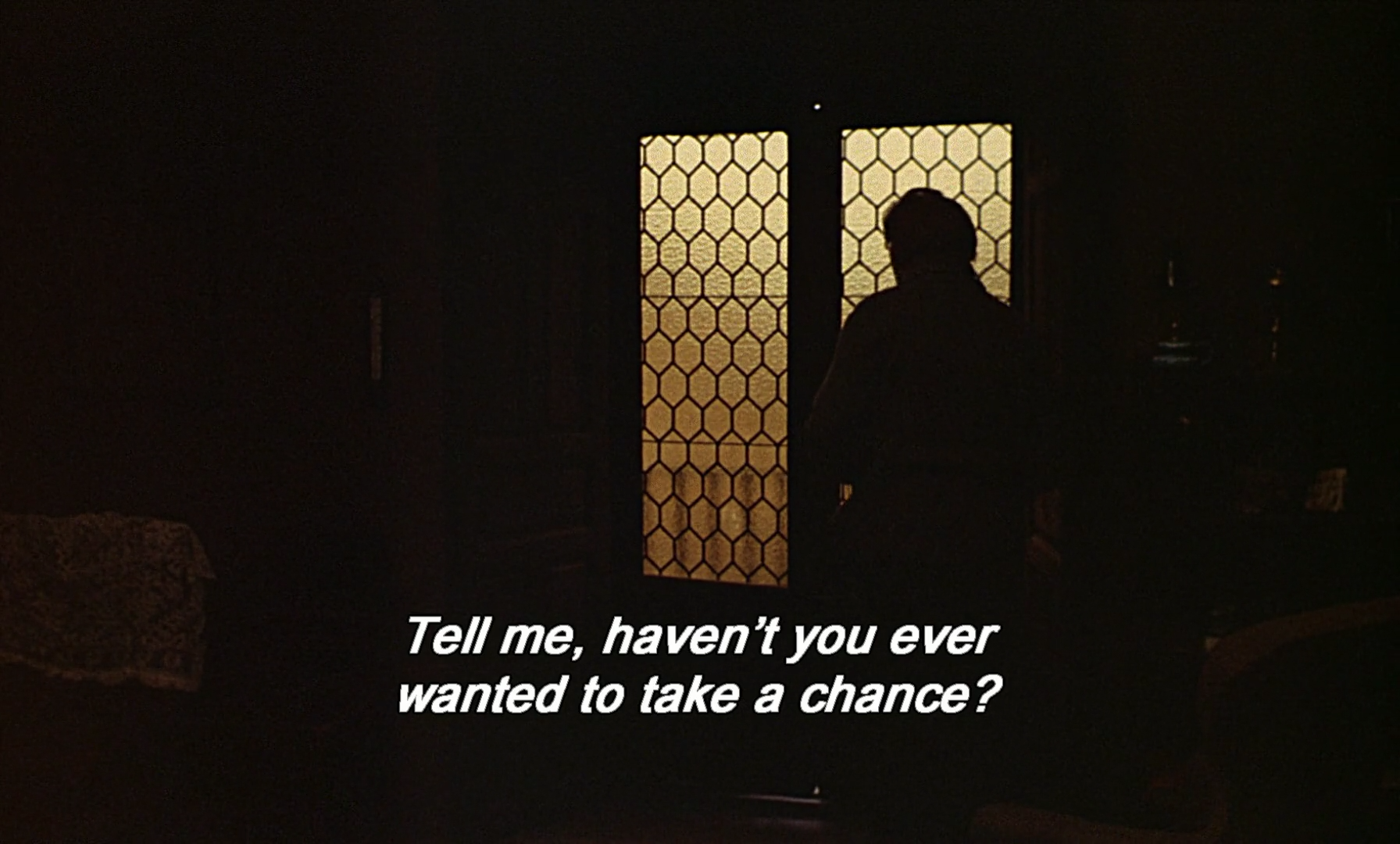

Victor Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive: "Yet if I could answer just one of these questions—what eternity is, for example—I wouldn't care if they called me mad."

The Spirit of the Beehive, directed by Victor Erice, screenplay by Victor Erice, Angel Fernández Santos, and Francisco J. Querejeta, cinematography by Luis Cuadrado, music by Luis de Pablo, and edit by Pablo G. del Amo.

“I try to achieve the beauty of truth. I always took as my motto what Robert Bresson said: ‘You don’t have to make images that are beautiful. You have to make images that are necessary.’” By invoking Robert Bresson’s philosophy on filmmaking, Victor Erice highlights the idea that the right choices in the right details is the key to creating the beauty of truth in cinema. Akira Kurosawa also alluded to this and referred to it as cinematic beauty, a beauty that is only obtainable through the efficient and effective use of film language, that when well-expressed produces a deep experience for the audience, and which is the very thing that inspires a filmmaker to create a film in the first place. For Erice, “Cinema may have no alternative other than to fall back on itself so that it may, once it has assumed its solitude, affirm itself in its dignity: a dignity conferred onto it by virtue of being the last of the artistic languages invented by man.” As an art form all to itself, cinema possesses its own unique artistic language, and it is by utilizing—making efficient and effective use of—this film language that Erice accomplishes the beauty of truth in his timeless films like The Spirit of the Beehive. Great films engage audiences with cinematic beauty through specificity of vision and economy of meaning. A great film results in cinematic beauty through the artist’s unique honing of a film to its essential poetry.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar: "Action Painting."

Au Hasard Balthazar, directed by Robert Bresson, screenplay by Robert Bresson, cinematography by Ghislain Cloquet, music by Jean Wiener, and edit by Raymond Lamy.

"Perhaps the idea came to me plastically because I am a painter. A donkey’s head seems to me something admirable. The plasticity, no doubt." Painting greatly inspired Robert Bresson, and his cinematic style is informed by his early years as a painter. Bresson admits that he "wanted to make a portrait" with Au Hasard Balthazar, and in this scene from his masterpiece, we get a window into how he feels about the art of cinema through the art of painting. In filmmaking, Bresson executes action painting, that is putting a cinematic world into movement, by emphasizing his paintbrush, that is his cinematic style. In the films of Bresson, the experience of the film itself becomes the art which calls back the hand that brought it into existence.

Essential Film Literature: Notes on the Cinematograph by Robert Bresson

(Note: Some links may be affiliate links. We may get paid if you buy something or take an action after clicking one of these.)

[Robert Bresson’s words] shine like stars, showing us the simple, troublesome way to perfection. - J. M. G. Le Clézio

Robert Bresson’s book on filmmaking Notes on the Cinematograph, known in other publications as Notes on Cinematography as well as Notes on the Cinematographer, is both a must-read and must-have for filmmakers and film lovers alike. As Donato Totaro writes in his article “Notes” on Notes on the Cinematographer:

“What is striking and unique about Bresson is how his writing is so much like his filmmaking: the elliptical style, the epigrammatic prose, the obtuse meanings, the material rigidity, the conciseness, the frugality of means. It is all there in both his work and his words. Andrei Tarkovsky, whose own work of film philosophy Sculpting in Time is among one of the finest written by a filmmaker, admitted that not all of the aesthetic and theoretical ideals he writes about were consummated in his film work. The only filmmaker whom he felt did match up with his theoretical ideal was Bresson. This is another indication of the uncanny similarity between Bresson’s writing and film style.”

A Man Escaped, directed by Robert Bresson.

In his films, Bresson emphasizes the functional and the economy of meaning. Precision and necessity are key elements to his cinematic style. As Susan Sontag says, “The power of Bresson’s films lies in the fact that his purity and fastidiousness are at the same time an idea about life, about what Cocteau called ‘inner style,’ about the most serious way of being human.” For him, art is about having everything in its right place. Therefore, Bresson prioritizes with deep intention and ambition the only elements that distinguish cinema from all other art forms: moving images and sound; he then focuses on using these elements in a utilitarian way.

A Man Escaped is a jailbreak thriller trimmed to its essentials in such a manner that Roger Ebert claims, “Watching a film like A Man Escaped is like a lesson in the cinema…I can’t think of a single unnecessary shot in A Man Escaped.” Au Hasard Balthazar is centered on a donkey and his Christ-like journey, of which Jean-Luc Godard describes as “the world in an hour and a half.” Although the films differ in story and theme, Bresson’s cinematic style is fully present in each: precision and necessity guided by the functional and the economy of meaning. This style is also felt throughout Notes on the Cinematograph, in what he highlights about the art of cinema and in how he presents his ideas (the original French version of the book is titled Notes sur le cinématographe). The following are excerpts:

Master precision. Be a precision instrument myself.

*

Two types of film: those that employ the resources of the theater (actors, direction, etc.) and use the camera in order to reproduce; those that employ the resources of cinematography and use the camera to create.

*

CINEMATOGRAPHY* IS A WRITING WITH IMAGES IN MOVEMENT AND WITH SOUNDS.

*

Cinematographic film where expression is obtained by relations of images and of sounds, and not by mimicry, of gestures and intonations of voice (whether of actors or of non-actors). One that does not analyze nor explain. One that recomposes.

*

Cinematographic film, where the images, like the words in a dictionary, have no power and value except through their position and relation.

*As will become clear, “cinematography” for Bresson has the special meaning of creative filmmaking which thoroughly exploits the nature of film as such. It should not be confused with the work of a cameraman.

Au Hasard Balthazar, directed by Robert Bresson.

Robert Bresson is a monumental figure in film history. As another great filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky, says, “Bresson has always astonished me and attracted me with his ascetics. It seems to me that he is the only director in the world that has achieved absolute simplicity in cinema. As it was achieved in music by Bach, in art by Leonardo. Tolstoy achieved it as a writer…Therefore, for me, he’s always been an example of ingenious simplicity.” That quality is also present in this pocket-sized bible on filmmaking and priceless look into the mind of an artist whose insights are captivating in their simplicity and depth. Pearls of filmmaking wisdom abound the book, which also contains lessons that apply to all art forms. Cinema is an experiential art, and Notes on the Cinematograph is an experiential read for those fascinated in Bresson’s set of principles and approach to film language, intrigued by the potential of filmmaking as an art form, and absorbed in their own cinematic style.

Be inspired by the additional excerpts present below, and immerse yourself in the world of Robert Bresson through the following link: Notes on the Cinematograph.

Metteur en scène or director. The point is not to direct someone, but to direct oneself.

*

An image must be transformed by contact with other images, as is a color by contact with other colors. A blue is not the same blue beside a green, a yellow, a red. No art without transformation.

*

Flatten my images (as if ironing them), without attenuating them.

*

Who said: “A single look lets loose a passion, a murder, a war”?

*

Two persons, looking each other in the eye, see not their eyes but their looks. (The reason why we get the color of a person's eyes wrong?)

*

Of two deaths and three births.

My film is born first in my head, dies on paper; is resuscitated by the living persons and real objects I use, which are killed on film but, placed in a certain order and projected on a screen, come to life again like flowers in water.

*

Shooting. To put oneself in a state of intense ignorance and curiosity, and yet to see things beforehand.

*

CINEMA draws on a common fund. The cinematographer is making a voyage of discovery on an unknown planet.

*

Let it be the intimate union of the images that charges them with emotion.

*

A too expected image (cliché) will never seem right, even if it is.

*

A sigh, a silence, a word, a sentence, a din, a hand, the whole of your model, his face, in repose, in movement, in profile, full face, an immense view, a restricted space…Each thing exactly in its place: your only resources.

*

Don't run after poetry. It penetrates unaided through the joins (ellipses).

*

Let it be the feelings that bring about the events. Not the other way.

*

Cinematography: new way of writing, therefore of feeling.

*

Someone who can work with the minimum can work with the most. One who can with the most cannot, inevitably, with the minimum.

*

Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.

*

Not to shoot a film in order to illustrate a thesis, or to display men and women confined to their external aspect, but to discover the matter they are made of. To attain that “heart of the heart” which does not let itself be caught either by poetry, or by philosophy, or by drama.

*

Images and sounds like people who make acquaintance on a journey and afterwards can not separate.

*

A single word, a single movement that is not right or is merely in the wrong place gets in the way of all the rest.

*

Don't think of your film apart from the resources you have made for yourself.

*

When a sound can replace an image, cut the image or neutralize it. The ear goes more toward the within, the eye toward the outside.

*

If a sound is the obligatory complement of an image, give preponderance either to the sound, or to the image. If equal, they damage or kill each other, as we say of colors.

*

Your film will have the beauty, or the sadness, or what have you, that one finds in a town, in a countryside, in a house, and not the beauty, sadness, etc. that one finds in the photograph of a town, of a countryside, or a house.

*

To TRANSLATE the invisible wind by the water it sculpts in passing.

*

The eye (in general) superficial, the ear profound and inventive. The whistle of a locomotive imprints in us a vision of the whole station.

*

Make visible what, without you, might never have been seen.

*

It is in its pure form that an art hits hard.

*

Not beautiful photography, not beautiful images, but necessary images, and photography.

*

Your film is not made for a stroll with the eyes, but for going right into, for being totally absorbed in.

*

Empty the pond to get the fish.

*

Cinematography films: emotional, not representational.

*

It is with something clean and precise that you will force the attention of inattentive eyes and ears.

*

Your public is not the public for books, stage shows, exhibitions, or concerts. Taste in literature, in theater, in painting, or in music is not what you have to satisfy.

*

From the clash and sequence of images and sounds, a harmony of relationships must be born.

*

The most ordinary word, when put into place, suddenly acquires brilliance. That is the brilliance with which your images must shine.

*

What I reject as too simple is the things that is important and that one must dig into. Stupid mistrust of the simple things.

*

The beauty of your film will not be in the images (postcardism) but in the ineffable that they will emit.

*

ECONOMY. Racine (to his son Louis): I know your handwriting well enough, without your having to sign your name.

*

The future of cinematography is to a new race of young solitaries who will shoot films by putting their last cent into it and without letting themselves be owned by the material routines of the trade.

*

Is it for singing always the same song that the nightingale is so admired?

*

Proust says that Dostoevsky is original in composition above all. It is an extraordinarily complex and close-meshed whole, purely inward, with currents and counter-currents like those of the sea, a thing that is found also in Proust (in other ways so different) and whose equivalent would go well with a film.

*

A great non-virtuoso pianist, of the Lipatti kind, strikes notes that are rigorously equal: minims, each the same length, same intensity; quavers, semiquavers, etc., likewise. He does not slap emotion onto the keys. He waits for it. It comes, and fills his fingers, the piano, him, the audience.

*

Bach at the organ, admired by a pupil, answered: “It's a matter of striking the notes at exactly the right moment.”

*

The pistol-shot of the painter’s eye dislocates the real. Then the painter puts it up again and organizes it in that same eye, according to his taste, his methods, his Ideal Beauty.

*

Equality of all things. Cézanne painting with the same eye and the same soul a fruit dish, his son, the Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

*

Cézanne: “At each touch I risk my life.”

(Note: As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.)