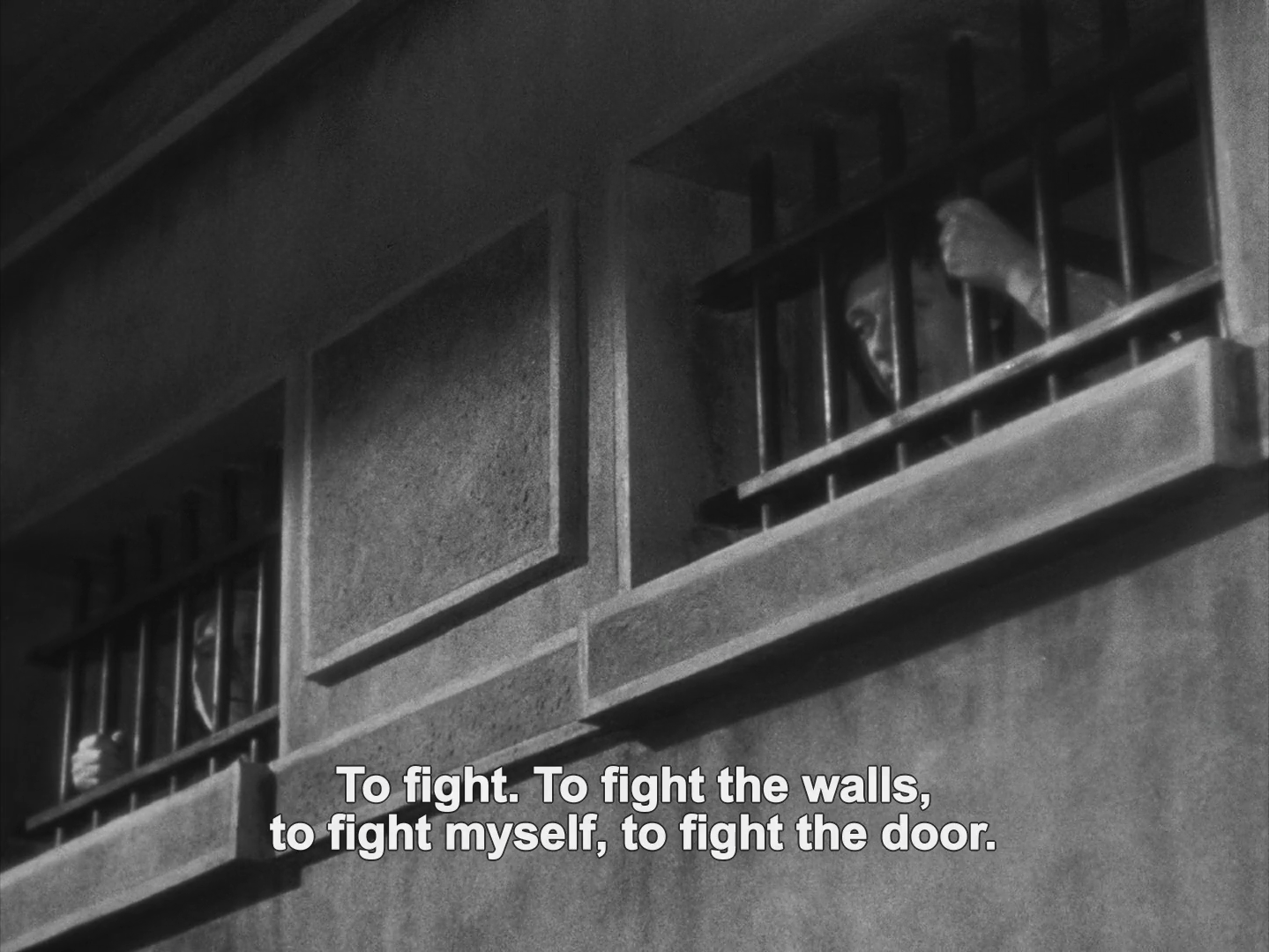

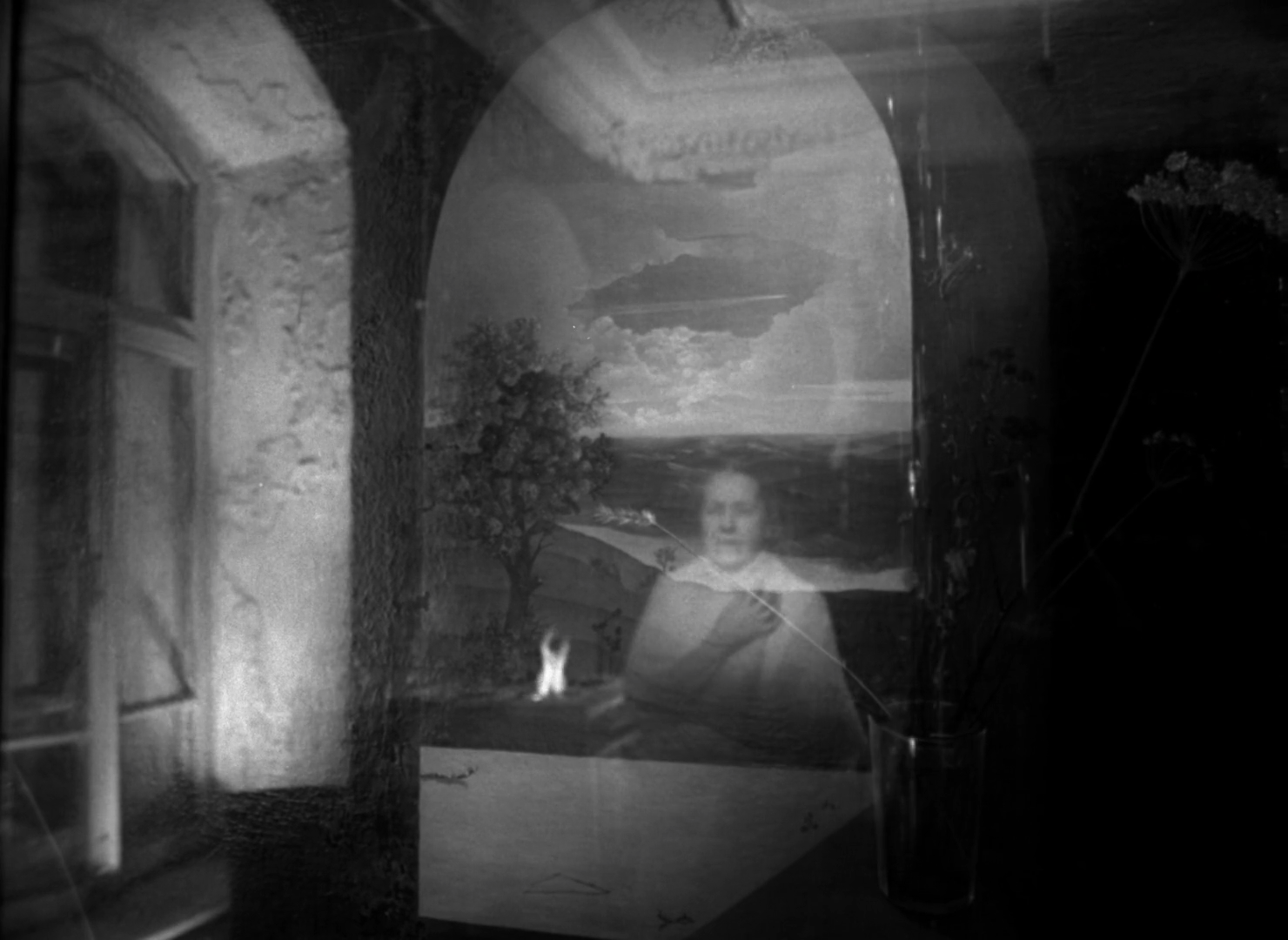

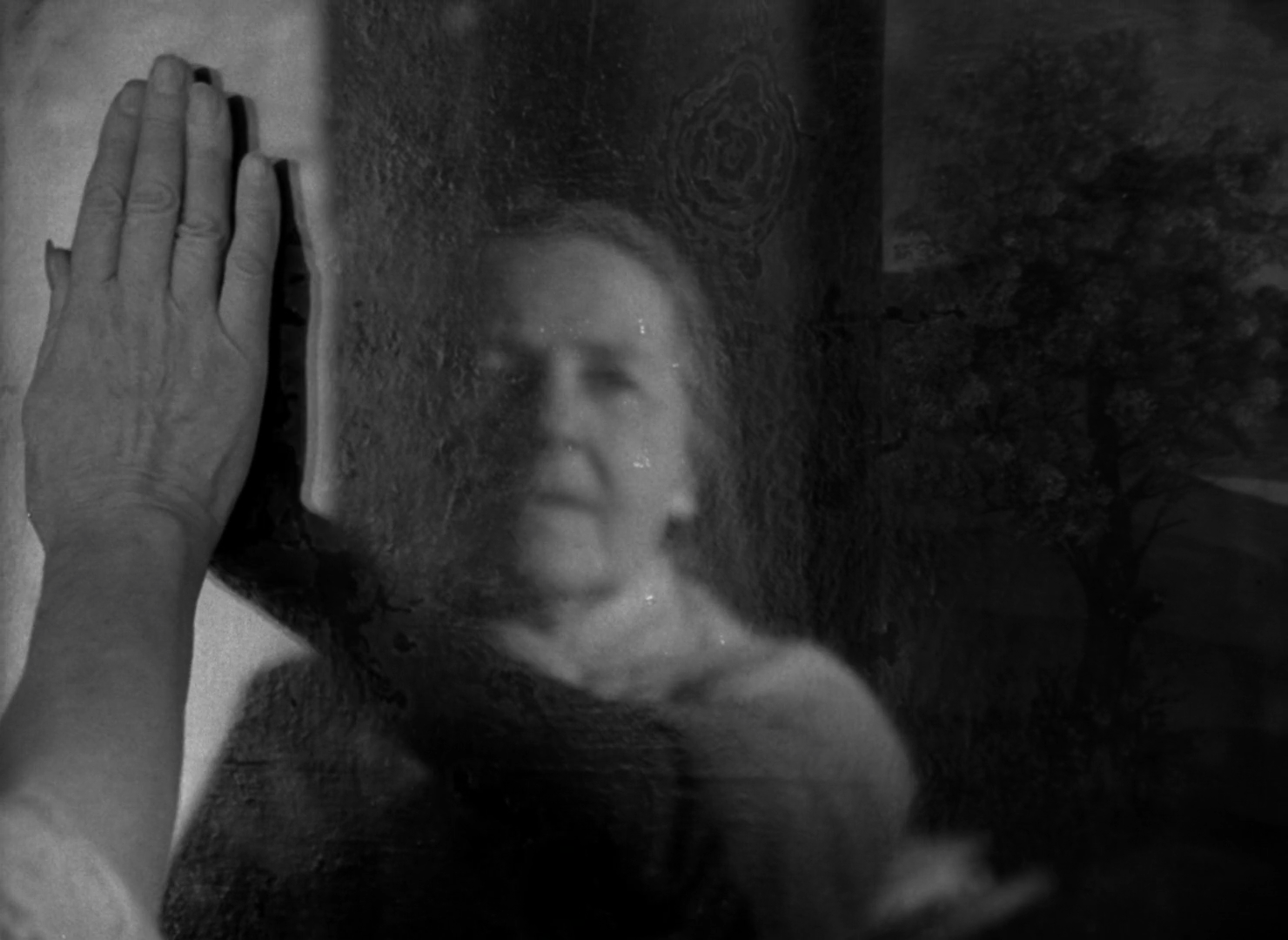

A Man Escaped, directed by Robert Bresson, screenplay by Robert Bresson, cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel, and edit Raymond Lamy.

When asked about the importance of Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky answered, “There are many reasons I consider Bresson a unique phenomenon in the world of film. Indeed, Bresson is one of the artists who has shown that cinema is an artistic discipline on the same level as the classic artistic disciplines such as poetry, literature, painting, and music. The second reason I admire Bresson is personal. It is the significance of his work for me—the vision of the world that it expresses. This vision of the world is expressed in an ascetic way, almost laconic, lapidary I would say. Very few artists succeed in this. Every serious artist strives for simplicity, but only a few manage to achieve it. Bresson is one of the few who has succeeded. The third reason is the inexhaustibility of Bresson’s artistic form. That is, one is compelled to consider his artistic form as life, nature itself. In that sense, I find him very close to the oriental artistic concept of Zen: depth within narrowly defined limits. Working with these forms, Bresson attempts in his films not to be symbolic; he tries to create a form as inexhaustible as nature, life itself.”

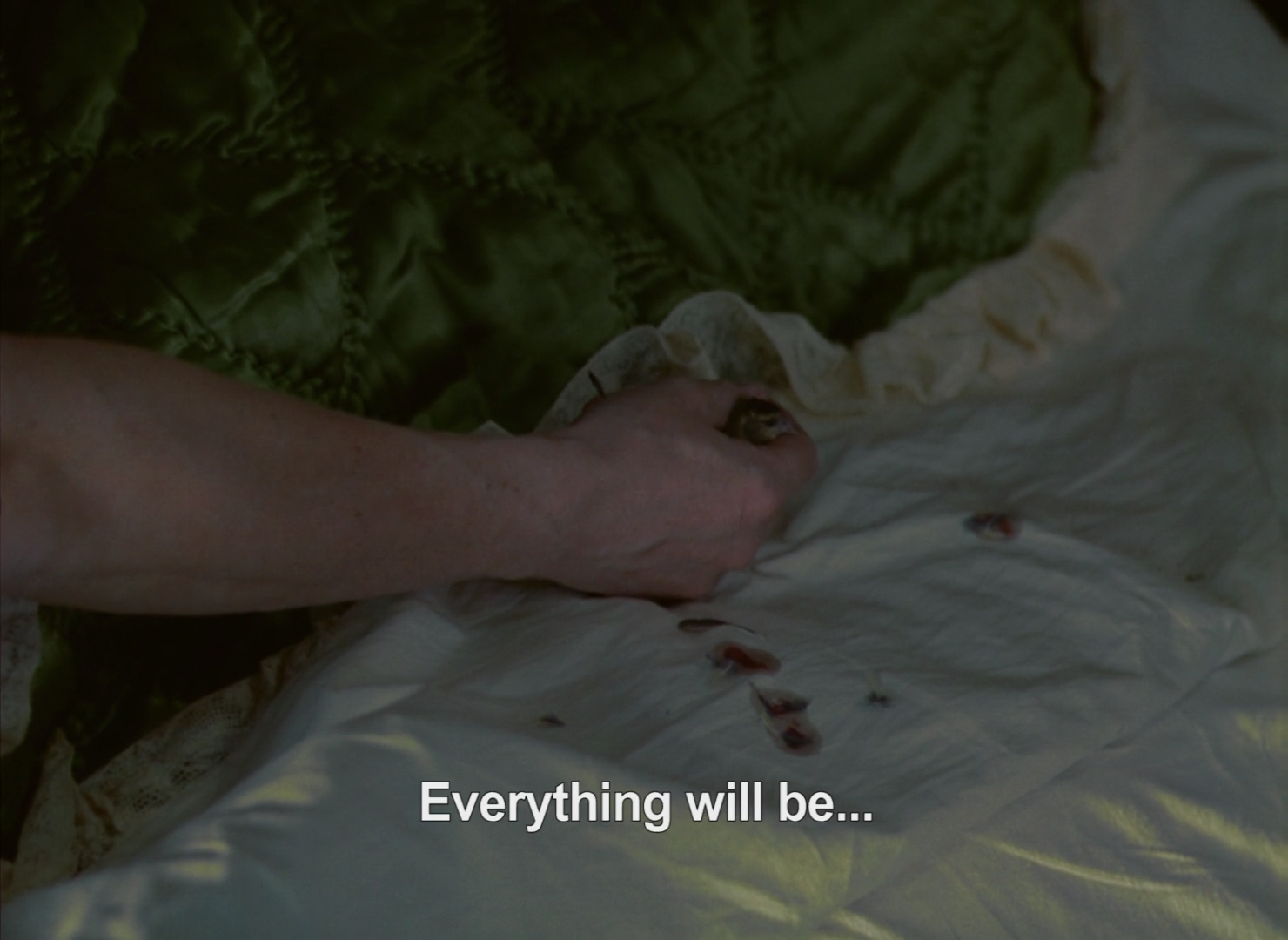

All true artists fight to convey the best path of expression within their art forms. Andrei Tarkovsky admired Robert Bresson because they shared a similar spirit when it came to filmmaking, a passion for shedding light on cinema as an art form with its own language and manner of engaging and creating profound experiences for audiences. Like Tarkovsky, Bresson epitomizes the authentic artist whose self-determination brings forth unparalleled art. He follows his vision, intuition, and own set of rules for filmmaking: he follows his own quest as an artist of cinema. His simplification or in other words purification of film elements is directed to reveal cinema not as a canvas for popular and commercial moviemaking but as a unique art form that generates unique experiences. The art and the cinematic experience together are the all-in-all. He himself expressed it as, “It’s not a question of understanding, it’s a question of feeling.” Direct yourself toward the experience to be felt by the audience, and the feeling will generate meaning.

The films of Bresson are also manifestations of the insight that you the artist are your greatest asset. One needs only to visit these Koan-like statements found in his Notes on the Cinematograph to become aware of the essence of the artist. “Metteur en scène or director. The point is not to direct someone, but to direct oneself.“ “Don't think of your film apart from the resources you have made for yourself.“ “Make visible what, without you, might never have been seen.” You are your greatest tool, your greatest resource.